Affinity Insights – Issue 12 April 2020

06/04/2020

Market Update – May 2020

19/05/2020

As a change of pace from our recent Covid-19 updates, we think it is worthwhile commenting on the performance of the US technology sector and some upside and downside scenarios.

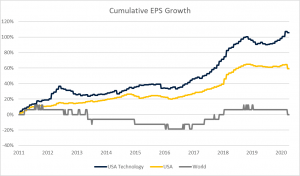

Technology stocks have materially outperformed the broader market since 2011, delivering a total return 50% greater than the US market and nearly 140% stronger than developed market equities. In many respects this has been justified by superior earnings growth. The technology sector in the US has delivered earnings growth far in excess of the US market (nearly double the cumulative increase since 2011). Versus global equities, which have failed to deliver any EPS growth in the past decade, the picture is even more stark.

Source: Drummond Capital Partners, Refinitiv, Datastream

Such impressive returns have raised questions about the sustainability of the technology sector – whether it is in a bubble or if the fundamentals justify the rally. On a P/E multiple basis, technology stocks in the US are more expensive than the broader market, trading at a 12% valuation premium to the broad US market and a 38% valuation premium against world equities. However, we note that the current multiple for technology stocks is well below the peaks reached in the Tech Bubble and the valuation premium above the broad US market is only slightly above the long run median (7%), while lower interest rates today justify a higher multiple premium for growth stocks.

Source: Drummond Capital Partners, Refinitiv, Datastream

The combination of the superior earnings growth and multiple expansion has taken the technology share of total US market capitalisation to around 25% – well below the peak reached in the Tech Bubble, but around 10 percentage points higher than where it sat between 2003 and 2015.

Perhaps more alarmingly, the five largest companies in the S&P500 now account for 20% of the market value of the index, doubling their weight since 2015. This concentration is higher than seen in the Tech Bubble and the highest since 1977, when IBM, GE, GM, AT&T and Exxon dominated the index. These five largest companies (Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet and Facebook) are all technology companies. While high concentration isn’t necessarily a bad thing, it does expose passive investors to much more idiosyncratic and sector risk than they might expect in a passive index investment.

Source: Drummond Capital Partners, Refinitiv, Datastream

There are company specific and broader macro reasons why investing in technology has been such as successful strategy. From a macro perspective, the dominance of technology companies makes perfect sense in a world where there is an absence of growth. The period since the Financial Crisis has seen anaemic economic growth everywhere and falling interest rates. If the “old economy” companies can only deliver EPS growth in line with the economy (low to mid single digits) and bonds are giving you close to zero everywhere, a technology company which is growing revenues at double digits looks very attractive. The same phenomena had seen credit spreads narrow to historic tights despite rising corporate leverage (search for yield), a buyback frenzy (which artificially juices EPS for the companies which participate) and the emergence of more leveraged systematic investment strategies and products (many of which blew up in the corrections of December 2018 and February 2020). Investors have been crowding into growth in the absence of any alternative.

On the company side, the success of investing in the technology sector reflects the strength of the underlying businesses. Their ability to generate outsized profits reflects a combination of first mover advantage, monopoly power, network effects and scale.

Consider this hypothetical example. Company X is the first to market with a new product or the first to leverage technology to deliver a service. Initially, Company X is uncontested in the space – there is literally no competition. This allows Company X time to build network effects[1] and scale, which eventually turn into monopoly power. With scale, incumbents have the resources to buy out innovative competitors before their products gain traction or reach market. They also have more resources to invest in their business, building walled gardens[2] and vertically integrated supply chains and hiring the best talent. They gain pricing power over customers and suppliers, able to extract more from consumers because there is no alternative product.

Technology companies have got to where they are by cannibalising existing businesses. For countless established companies, their corporate strategy needs to be completely re-written to deal with the future. Many cannot compete and will go out of business, with their sales and profits being captured by the dominant technology player in each sector. You do not want to own the businesses which will fail in this environment, you want to own the businesses which destroy them.

If the above leaves a bad taste in your mouth, you aren’t alone. That brings us to the key risk in investing in these businesses: The majority are all hugely exposed to changes in government regulation and anti-trust. Historically in the United States, companies which held dominant positions similar to today’s technology leaders were broken up by the Government. Many technology companies have gained success by skirting labour laws in many countries, treating what would normally be defined as an employee as a contractor – allowing them to pay lower wages than their competitors. Access to personal data (usually without the user’s informed consent) has allowed many technology companies to obliterate existing marketing and media companies, which have comparatively little access to data.

Below, we outline a few hypothetical scenarios which could damage the sector’s prospects. Certainly, some of this risk is already embedded in company valuations. However, a dramatic change in the way governments are responding to the dominance and power of the technology sector would take much of the shine off the sector.

- Anti-trust: A Democrat administration in 2021 would likely be much more proactive on anti-trust than the Republican party has been. Many of the big tech companies have multiple core businesses wrapped up into one infrastructure. For example, Amazon is a retail/delivery company, a provider of web services and an advertising company. Apple is a gadget manufacturer, a content provider and a software company. If these companies were broken into key components, they are likely to be in a less dominant position to restrict competitors from entering their space. They will also lose some of the synergies they enjoy from the sharing of user data across the business units.

- Privacy: It is very unlikely that the average Facebook, Apple or Google user understands how much personal data these companies collect when you use their services and devices and the value they monetise by selling it to third-party companies. How much they know about you goes beyond creepy and it is easy to imagine government policy designed to better inform users about what they are giving away or prevent or restrict the sale of this data.

- Employee rights: We could see government legislation which ensures that contract workers are treated the same as employees, which would hurt the margins and survival prospects of many technology businesses.

In addition to the above, while there may not be a bubble in technology sector valuations in the public markets, prior to the Covid-19 outbreak private markets were looking very frothy. Private markets are much more opaque than public markets and some have suggested that valuations for venture companies have been artificially inflated by investors willing to pay “whatever it takes” just to get invested. The strategy is validated when the next investor (sucker) in the line funds another round at a higher valuation still. Maintaining this momentum is impossible in the current market environment and some of the pessimism may bleed over to the listed technology sector.

There is also a strong potential upside scenario for the sector. As mentioned above, the valuation premium for technology is only slightly above the long run median. In the Tech Bubble investors were willing to pay a multiple of 45 times earnings for the sector (around double the current forward PE) – and that’s when these companies generated little to no earnings. We saw a similar phenomenon in the 1960s and 1970s, where the Nifty 50 valuations soared to between 50 and 90 times forward PE by 1972. Companies populating this list included Avon, Disney, McDonald’s, Polaroid, and Xerox. These companies were strongly favoured by investors due to their high profits, double digit growth rates and strong balance sheets[3]. While both of these bubbles deflated into protracted bear markets, with valuations normalising, this time may be different. Regardless, if this scenario were to occur, there is a lot more upside to capture before the bust.

We think that the earnings and valuation profile continue to suggest outperformance of the technology sector will continue. We will certainly be monitoring trends in government policy to gauge whether the tide on technology is turning via increased government intervention and regulation.

[1] A network effect is a phenomenon whereby increased numbers of people or participants improve the value of a good or service. There more users, the better the user experience.

[2] A walled garden attempts to keep the users of a product within the ecosystem of the company, providing a 1 stop shop for all related peripheral and core products and services. The walled garden can also prevent users from accessing the products and services of competitors via physical and technological barriers.

[3] http://economics-files.pomona.edu/GarySmith/Nifty50/Nifty50.html

The information contained in this article is current as at 18/05/2020 and is prepared by Drummond Capital Partners ABN 15 622 660 182, a Corporate Authorised Representative of BK Consulting (Aust) Pty Ltd (AFSL 334906). It is exclusively for use for Drummond clients and should not be relied on for any other person. Any advice or information contained in this report is limited to General Advice for Wholesale clients only.

The information, opinions, estimates and forecasts contained are current at the time of this document and are subject to change without prior notification. This information is not considered a recommendation to purchase, sell or hold any financial product. The information in this document does not take account of your objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on this information recipients should consider whether it is appropriate to their situation. We recommend obtaining personal financial, legal and taxation advice before making any financial investment decision. To the extent permitted by law, Drummond does not accept responsibility for errors or misstatements of any nature, irrespective of how these may arise, nor will it be liable for any loss or damage suffered as a result of any reliance on the information included in this document. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

This report is based on information obtained from sources believed to be reliable, we do not make any representation or warranty that it is accurate, complete or up to date. Any opinions contained herein are reasonably held at the time of completion and are subject to change without notice.