Affinity Insights – Issue 13 October 2020

30/10/2020

Reading the Crystal Ball for 2021

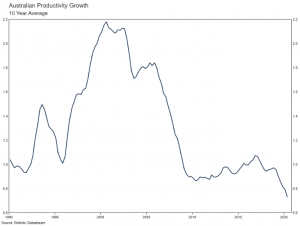

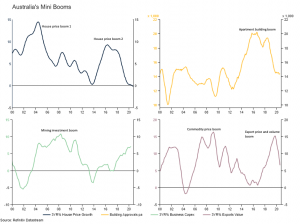

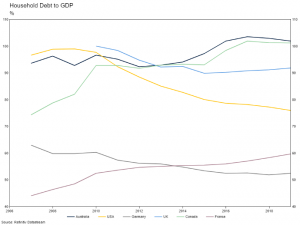

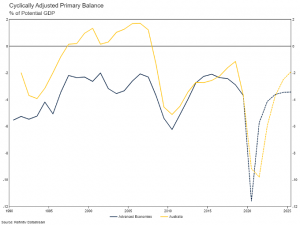

24/11/2020 After many long months of some of the world’s strictest lockdowns, Victoria appears to be on the cusp of eliminating Covid-19 for the second time in eight months, aligning it with the rest of Australia. Ignoring the public health trade-off between lives saved versus damage by lockdowns, we must ask ourselves – what does this mean for domestic markets versus the rest of the world? The answer isn’t as simple as less virus = outperformance. Australia’s long track record of strong investment returns can in part be attributed to its nature as a flexible, open economy. Very important sectors of the economy, such as overseas tourism and education need open borders to function. The housing construction industry relies on overseas migration. Many businesses require skilled migrant employees. Meanwhile, state governments have demonstrated they will accept zero Covid-19 risk. Absent a very effective vaccine being distributed through most of the population, or an increase in risk tolerance, does Australia risk turning itself into a hermit kingdom while the rest of the world moves along without us after the coming Northern Hemisphere winter? Australia has an impressive economic track record Australia had been the lucky country until Covid-19, avoiding a technical recession in the Financial Crisis and enjoying strong economic growth since the 1990s. Between 1995 and 2019, real GDP in Australia rose 114%, compared with a 83% increase in the USA, a 51% increase in Europe and a 23% increase in Japan. This growth was initially sown by the significant economic reform agenda in the 1980s and 1990s. This saw 10-year average productivity growth in Australia double in the 1990s versus the 1980s. Since 2000, Australia has ridden a series of mini booms. Exceptional house price growth in the early 2000s driven by lower interest rates and banking sector reform meaningfully boosted household wealth through this period – boosting retail spending and confidence. When the first house price boom in Australia began to ease in response to higher interest rates, booming commodity prices driven by demand in China drove a mining investment super-cycle and boosted national income substantially. The investment boom saw wages growth for skilled employees explode higher. The benefits of higher commodity prices flowed to governments through royalty payments and corporate tax revenues which were then recycled to households in the form of substantial tax cuts. As commodity prices fell and investment peaked, we embarked on an apartment construction spree. Australia’s annual population increase accelerated from a 5-year average of around 225,000 persons in 2005 to around 380,000 persons in 2013. The extra people needed somewhere to live, and apartments provided the solution. Building approvals rose by more than 60% between 2012 and 2016. However, apartments take a long time to build, meaning supply came onto the market slowly. The delayed supply, lower interest rates post financial crisis, demand from Chinese buyers and looser domestic lending standards converged and drove a second house price boom. As house prices began to taper off in response to a post Hayne Royal Commission tightening of lending standards and increased apartment completions, supply issues in Brazil saw iron ore prices again start to rise meaningfully, again boosting national income. This also coincided with a state government infrastructure spending spree. Through this entire period, very strong population growth, driven by international migration also supported growth. Success has bred excess Of course, all that success hasn’t come without a cost. Very high export prices saw the A$ quite strong in the early 2010s, to the detriment of other exporters. Mining investment crowded out and increased the cost of other infrastructure and capex projects during the boom. Two decades of house price growth well in excess of income growth has seen younger households burden themselves with a lifetime of debt and older households tap into retirement savings to fund deposits to afford a residence in metropolitan NSW or Victoria. Perhaps many years of growth have given households the confidence to lever themselves to the gills. Regardless, Australian household debt to GDP is now among the highest in the world. The fiscal largess following the mining boom also transformed what had been a largely balanced fiscal position into a structural deficit. However, this deterioration in the fiscal position has simply moved Australia into a position comparable to rest of the advanced economies. Importantly, the level of outstanding government debt in Australia remains modest (unlike our households) compared to other advanced economies. This gives the Government significantly more room to stimulate the economy in times of need than many other countries. Controlling Covid-19 will leave us with some uncomfortable choices In the short term, Australia’s success in eliminating Covid-19 should see our markets hold up against Europe and the US in the face of their uncontrolled Covid-19 spread. Between 9 July (the beginning of second lockdown) and 1 October (when Victoria hit a low of 5 daily cases), Australian equities underperformed global equities by 6.5%. The Australian economy should recover sharply through our summer as restrictions in Victoria are lifted, ideally seeing some of this underperformance reversed. The RBA is also expected to ease policy further next week. In comparison, European countries in particularly are re-establishing ‘lite’ lockdowns or ‘circuit breakers’, shutting down bars and restaurants and restricting gatherings. In the US, markets also face the prospect of an uncertain election outcome, delayed stimulus and the damaging effect to confidence from the inadequate response to Covid-19 control. However, as we move into 2021, more than likely with a partially effective vaccine beginning to be rolled out, Australia may find itself in an awkward position. A vaccine which is 50%-75% effective and is rolled out to 75% of the population will clearly leave some gaps in terms of coverage[1]. The vaccine could be less effective at reducing disease severity in high-risk cohorts than in those less at risk. The vaccine may also reduce symptoms, but not prevent transmission. With a vaccine in hand, there is a chance that if international borders were opened without mandatory quarantine, Australia could see new outbreaks and subsequent Covid-19 deaths. Travel bubbles between Covid-19 free regions have been flagged as a potential solution to this problem. However, outside of China, there aren’t really any significant candidates. China is obviously a very important source of foreign students and tourists for Australia and is for the most part Covid-19 free (though a recently discovered outbreak in Kashgar of 137 workers in a clothing factory raises questions). However, the implementation of a travel bubble between China and Australia would require Australian politicians to put more faith in their Chinese counterparts than they do their interstate brethren. This seems unlikely at the moment. Rapid Covid-19 testing at airports could add another layer of safety and is being used in other countries and jurisdictions. However, these tests are not 100% accurate and the risk of being forced into Australian quarantine if you happen to test positive on arrival when you were expecting to be diving the Barrier Reef instead is a risk many will not take. There isn’t an easy solution to this problem. Australia’s hard work and success at containing Covid-19 still leaves a difficult path ahead for the economy. It is extremely difficult to assess the damage to the economy from closed borders. However, we can make a very high-level assessment based on population growth and tourism. In an absolute sense, overseas migration in Australia has been responsible for around half of our overall population growth in the past decade. Assuming this directly translates into GDP growth, which is a reasonable assumption, a complete halt (which is admittedly unlikely medium term) to net overseas migration would shave around 80bps per annum from GDP growth, around 1/3rd of the annual average in the past decade. International tourism and education together represent around 4% of the Australian economy. If overseas borders remain shut, the Government will need to provide support to the tourism, education and construction sectors and the myriad of businesses supporting them. Even with this support, economic growth will remain lacklustre until the borders re-open, driving relative market weakness. Weak growth, expanding deficits and reduced services exports should drive currency weakness. It is also likely that parochial policy by many of Australia’s Premiers has done long-lasting damage to business confidence. Only an exceptionally brave entrepreneur would set up a business which relies on the free movement of people in this country at the moment. Australians are also (with limited exceptions) still banned from travelling overseas which is an untenable medium-term situation for many businesses which rely on overseas demand for their goods and services. Then again, maybe Australia will strike it lucky once more and the unlikely combination of a very effective vaccine and new treatments will allow us to again accept migrants, tourists and students with few restrictions. More likely, Australians and their governments will eventually need to accept some level of Covid-19 risk in order to stop the country becoming an international pariah. Other news The new President elect, Biden is set to enter the White House in January 2021. Please click here for our previous article regarding the implications of the US election on the economy. Our office will be closed for the festive season from 12:00 PM Wednesday 23rd December 2020 and returning on 9:00 AM Monday 11th January 2020. [1]https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/oct/21/covid-vaccine-immunisation-protection?CMP=share_btn_tw The information contained in this Market Update is current as at 06/11/2020 and is prepared by Drummond Capital Partners ABN 15 622 660 182, a Corporate Authorised Representative of BK Consulting (Aust) Pty Ltd (AFSL 334906). It is exclusively for use for Drummond clients and should not be relied on for any other person. Any advice or information contained in this report is limited to General Advice for Wholesale clients only. The information, opinions, estimates and forecasts contained are current at the time of this document and are subject to change without prior notification. This information is not considered a recommendation to purchase, sell or hold any financial product. The information in this document does not take account of your objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on this information recipients should consider whether it is appropriate to their situation. We recommend obtaining personal financial, legal and taxation advice before making any financial investment decision. To the extent permitted by law, Drummond does not accept responsibility for errors or misstatements of any nature, irrespective of how these may arise, nor will it be liable for any loss or damage suffered as a result of any reliance on the information included in this document. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This report is based on information obtained from sources believed to be reliable, we do not make any representation or warranty that it is accurate, complete or up to date. Any opinions contained herein are reasonably held at the time of completion and are subject to change without notice.Still The Lucky Country?