Market Update – August 2020

04/08/2020

US Election Issues & Implications

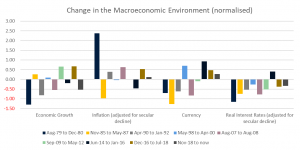

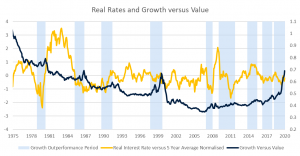

21/09/2020 The recent rally in global growth stocks has now driven the largest outperformance vs value stocks on record. The gap between the valuation of the most expensive stocks and the cheapest stocks, is also at or very near record highs depending on which measure you use. In some ways, this feels like the heady days of the tech bubble. There is certainly anecdotal evidence that the rally is being pushed by speculative retail investors. In our Strategic Asset Allocation Review, we characterised the most likely forward environment as one suffering from low growth and low interest rates. At least since the financial crisis, growth companies have been able to deliver earnings in a low economic growth environment. We also like the structural thematic around technology companies, which we wrote about in more detail in our Both Sides of the Technology Sector Coin Market Update. In this Market Update, we outline some of our thinking around the divergence between growth and value companies and prospects for the future. The Macroeconomic Environment Many explain the outperformance of growth stocks by pointing to the current macroeconomic environment, characterised by very low interest rates and weak growth. To test this hypothesis, we have mapped periods of growth outperformance against the conditions present before and during growth rallies. This is shown in the figure below. For every period of growth outperformance since 1975, we show what the change in the state of the economy was relative to the period prior. For every variable except for real interest rates, there is no clear relationship. We have undertaken the same analysis cutting the data in a number of different ways and using the US market, rather than the world market, but the conclusions are largely the same. Source: Refinitiv, Drummond Capital Partners The theory behind why a lower real interest rate should support a growth company is straight forward. A value investor at their core believes the assets of a business are undervalued relative to what the market is currently pricing. A growth investor believes the future cash flows of a business are undervalued relative to market pricing. Lower real interest rates increase the value of the cash flows of a growing business because the interest rate which they are discounted against is lower. Because you do not need to discount the value of currently held assets when valuing a company, value stocks do not face the same benefit. The problem with pinning your hopes on real interest rates as the guiding determinant for value outperformance is shown in the chart below. It plots our normalised real interest rate series and the growth versus value performance. It is clear that while in periods of growth outperformance real interest rates tend to trend lower, there are many periods in history in which real interest rates fall and value outperforms growth. Indeed, when we apply regression analysis to the two series, we find no statistical predictive power. Source: Refinitiv, Drummond Capital Partners So, if the data will not explain what is going on from a historical perspective, where does that leave us? There are a number of more qualitative hypotheses which could address the outperformance. The Tech Industrial Revolution While personal computing has been around for many decades, like any other industrial revolution, it takes time for the impact of a new technology to completely permeate into the way consumers and businesses operate. Industrial revolutions also happen pretty infrequently (this is the third or fourth depending on how you define it since the 1700s). It might simply be the case that in periods of rapid technological progress, growth outperforms value as the companies taking advantage of new technologies displace older, more established rivals. The counter to this argument is that there has always been technological innovation, and from a productivity growth perspective, the current period is actually underwhelming when compared with much of history. Perhaps that is the case, but in this instance there seems to be a pretty clear linkage between technological supremacy and the ability to grow and deliver earnings. Many of these companies are using technology to disrupt and cannibalise established businesses. This trend has been amplified by the monopoly power increasingly enjoyed by the largest technology companies, a subject we have addressed in a previous note. This is very different to the tech bubble, where the companies achieving very high valuations failed to deliver any earnings and subsequently collapsed in value. Value Has Simply Stopped Working The seminal Fama/French paper on the value premium (alongside size, leverage and earnings yield) was based on data between 1963 and 1990. Since value was identified as a systematic investment factor, performance has been quite poor. It could be the case that its identification and implementation across investor portfolios worldwide (who doesn’t own a value manager?) has arbitraged the excess return premium away. The increasing use of passive investment vehicles may also be driving some of the return differential. Most passive investment is managed against market capitalisation weighted indexes. The largest companies in a market cap index tend to be more growth than value orientated. Value = cheap and cheap = smaller market cap. While the concentration of tech at the top of the index is growing by the day, the figure below demonstrates that mega cap companies are quite common. Moreover, these mega cap companies can dominate the top of the market for many decades and Amazon, Google, Facebook and Visa are all new additions to the top ten. Source: Dimensional While the historical data does not necessarily support a long-term causal relationship between macroeconomic variables and equity factor performance, we don’t want to discount the possibility that it will matter in the future. Given this, we think that the most likely time for a continual outperformance of value will occur if we enter a rising growth and interest rate environment. However, this is our qualitative assessment, rather than being backed by statistics. There aren’t many other obvious catalysts for a reversal into value stocks. The election of a US Government committed to antitrust regulation, worker rights and personal data privacy is a clear and present risk to some of these stocks (but not all). Perhaps the announcement of a Covid vaccine would drive a meaningful rally in beat up airline and tourism stocks, but these names are pretty small within the market. Even after the vaccine we will be left in a world where it is easier and quicker to get things delivered by Amazon than Kmart, cloud storage and GPU capacity demand is basically endless, businesses are forced to advertise in the three big online marketplaces, high capital and research costs lock out emerging chip manufacturers and non-cash payments are dominated by a few key intermediaries. While the price action might feel like the tech bubble, these companies deliver earnings and control the markets in which they operate. Maybe they should trade at 40 times earnings. Nothing else is growing and many of these companies have a demonstrated track record of delivering earnings growth across a variety of economic environments. If these companies continue to deliver double digit earnings growth, they will quickly grow into their lofty multiples. We saw a similar outcome with following the Nifty 50 bubble, which was driven by growth companies such as Coca-Cola and McDonalds, which eventually grew into their PE ratios – though not without considerably volatility. That said, recent price action feels very peaky. Even ignoring the Teslas and Nikolas of the world, the Apple forward PE has risen to 38 times earnings, versus 25 times at the beginning of the year. Many other tech companies have also experienced stellar rallies. Meanwhile, Qantas is trading at a PE of 7, versus 14 before the Covid outbreak. At some point, the world will return to normal and it will make sense to buy a company at half price rather than double price. Cheap companies are the cheapest they have ever been. Expensive companies are the most expensive they have ever been. Despite this, it doesn’t feel like the time to divest entirely from growth. We are not yet certain that global growth is going to accelerate sustainably to a point where the cheap companies are unjustly so. The information contained in this Market Update is current as at 02/09/2020 and is prepared by Drummond Capital Partners ABN 15 622 660 182, a Corporate Authorised Representative of BK Consulting (Aust) Pty Ltd (AFSL 334906). It is exclusively for use for Drummond clients and should not be relied on for any other person. Any advice or information contained in this report is limited to General Advice for Wholesale clients only. The information, opinions, estimates and forecasts contained are current at the time of this document and are subject to change without prior notification. This information is not considered a recommendation to purchase, sell or hold any financial product. The information in this document does not take account of your objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on this information recipients should consider whether it is appropriate to their situation. We recommend obtaining personal financial, legal and taxation advice before making any financial investment decision. To the extent permitted by law, Drummond does not accept responsibility for errors or misstatements of any nature, irrespective of how these may arise, nor will it be liable for any loss or damage suffered as a result of any reliance on the information included in this document. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This report is based on information obtained from sources believed to be reliable, we do not make any representation or warranty that it is accurate, complete or up to date. Any opinions contained herein are reasonably held at the time of completion and are subject to change without notice.A return to value?