Market Update – June 2021

28/06/2021

Market Update – October 2021

18/10/2021Regulating the Technology Sector

To the bewilderment of many in the investment community, the Chinese Government appears to be systematically targeting many of their largest and most successful companies with punitive regulatory actions. Some of the highlights include:

Anti-monopoly fines against Tencent, Baidu (China’s Google) and Alibaba (China’s Amazon).

Suspending the Ant IPO (China’s PayPal) and “disappearing” Jack Ma (the founder of Alibaba and China’s richest person) for a few months.

Removing the Didi (China’s Uber) application from Chinese app stores.

A crackdown on the online education sector, banning for-profit school curriculum tutoring.

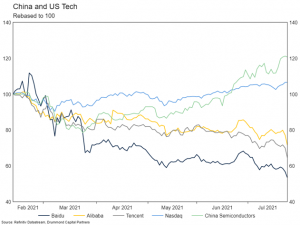

The subsequent re-pricing of regulatory risk has driven a sharp divergence in performance between the largest Chinese tech companies and their US counterparts.

We think this re-pricing is warranted. The regulatory push has been across four broad areas. Improving capital requirements in fintech, reducing monopoly power, preventing misuse of personal data and ensuring corporate behaviour doesn’t contravene Government policy priorities. Improving financial stability, protecting consumer privacy and breaking up monopolies are all noble goals which arguably should be pursued by regulators in the US. The larger issue for markets is the last item on the list – aligning the goals of companies with the Government.

Active industrial policy in China is not new, the Government is now up to its 14th Five Year Plan. Post 1978 reform era Plans had tended to specifically target high levels of economic growth and industrial manufacturing capacity. The Government believed that following the growth model of other rich Asian economies (Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore) led by investment in manufacturing capacity would drive economic development and transform China into a rich economy. In the post Financial Crisis period, the costs of growth at any cost were becoming apparent. Debt levels were extremely high, facilitated by unregulated lending against uneconomic investments. As a result, subsequent Plans have moved towards a more balanced growth model. These targeted higher consumer spending and also addressed environmental and social concerns more explicitly. Thus began the deleveraging period, where the Government increased regulation in the financial sector and injected some risk into the debt issued by state owned enterprises (SOEs). More recent Government commentary has shifted focus from consumer led growth towards targeting high value add technology and manufacturing. This would see Chinese economy look more like Germany or Japan than the US. This is where we bring you back to the chart above. While China’s answer to the largest US tech companies have all collapsed in value, the China semiconductor producer index has outperformed the Nasdaq.

The Chinese Government has a long-term vision for the country, and when they think of global technological supremacy, what comes to mind probably isn’t sleek phone design, speedy delivery of consumer goods, funny videos, society destroying social media or consumer advertising. The largest technology companies in the US make lots of money for their investors, but they aren’t “good” for society or even the economy. The leader of China, with a 50-year horizon, probably doesn’t want the best and brightest programming artificial intelligence (AI) to sell knick-knacks or undermining Party control by developing media platforms which facilitate unregulated speech online. They should be working in materials science and physics, and programming AIs which support broader national goals.

The key difference between now and 15 years ago is that a pure growth model closely resembles the sort of capitalism western investors are used to, with the added benefit of additional government support for national champions. Now, the economy has become much more Government directed. The rights of shareholders are secondary to the political goals of the Government and under Xi Jinping, these goals have shifted towards authoritarianism and nationalism and away from pure economic growth. This makes investing in Chinese companies mechanically more difficult. Whether or not the company will fall afoul of the Government is now as important as determining if it is a good business. This means an additional risk premium for holding Chinese stocks is required.

The Credit Cycle

China’s post Covid growth recovery has been disappointing. There are several reasons for this, including tightening financial conditions from mid-2020, supply chain disruptions and Covid lockdowns, and a cautious consumer suffering from historically weak income growth. Some of this weak growth has been intentional. The Government has been restricting access to credit via the shadow banking system since 2018. However, in early 2020 that policy was relaxed for around six months before resuming with gusto. The Government also allowed an abnormally high number of SOEs to default in 2020, seeing credit spreads widen somewhat.

The slow recovery has been most keenly felt by consumers. Growth in retail sales in China has been eclipsed by the US since early 2020, despite a much more severe Covid outbreak in the US and a much higher natural rate of growth in China. Topping off the weak consumer recovery, overall economic data in China began to deteriorate sharply in June and July as shown in our Asia Growth Barometer:

The Government acted quickly, with the PBOC (China’s central bank) surprising the market with a cut to the Reserve Requirement Ratio, freeing up around RMB 900 billion worth of liquidity. The market now expects a further cut to the RRR later in the year.

A key question is whether this easing represents a concerted effort to reflate the economy, or whether it is simply a fine-tuning of policy. At this stage the latter seems more likely. Triggering an increase in debt via another credit cycle doesn’t resolve any of the long-term goals of the Government. In addition, adding more debt to the already over-leveraged system also makes the eventual resolution of China’s longer term financial system issues more difficult and increases the probability of an outright crisis. This probably means limited upside to Chinese equities, which have tended to benefit from the credit booms.

Cracks in the Financial System

Cynics have been calling for a collapse in the Chinese financial system for many years and have been persistently wrong. The economy has all the hallmarks of an accident waiting to happen. Huge amounts of debt, delivered by an opaque financial system, prop up unproductive state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The housing market is perversely plagued by both unaffordability and ghost cities. Bad borrowers are regularly bailed out lest true credit risk get priced into the system. Previous attempts to rebalance growth away from investment towards consumer spending by adjusting the provision of credit usually leads to a sharper than desired reduction in overall growth, seeing the credit taps get turned back on. Despite the above, the Government has a good track record of avoiding outright policy failures and preventing a collapse. Few credible China watchers think a crisis is likely, but it is always a possibility.

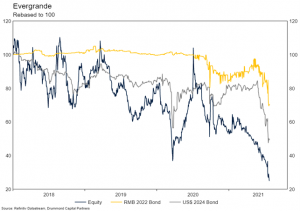

Recently, some pretty sizeable cracks have begun appearing within the financial system. Evergrande (one of China’s largest property developers) and China Huarong Asset Management (an asset manager set up by the Government to hold distressed assets) are on the verge of failure without Government support. The total liabilities of Evergrande may be as high as $300 billion and it seems increasingly likely that bondholders will not be repaid in full. USD bonds are trading at around 50 cents on the dollar, the Jiangsu Province Court recently froze bank deposits and authorities in Shaoyang froze sales because a lack of funds in pre-sale accounts.

China Huarong Asset Management is in turmoil following the conviction and execution for corruption of its Chair Lai Xiaomin six months ago. The value of assets on its balance sheet is in question and it has yet to release financial accounts for 2020. Its bonds have also fallen sharply in value and investors are waiting on clarity from the Government regarding its support of the company. The other state backed distressed asset managers have avoided any contagion. However, if the Government chooses to not back Huarong the removal of the of the implicit guarantee would likely impact their cost of funding.

These events in isolation are not necessarily cause for concern. Both companies (like many others have been in the past) could be resolved by the Government with minimal overall disruption to the financial system. However, both fit in the “too big to fail” category and there is a low risk that the Government could mis-manage their failure. This could trigger a more systemic shock through the Chinese financial system, which would trigger a severe market reaction domestically and overseas.

Although the China bears probably won’t get the collapse they are aiming for, there will still be some reckoning. Some part of the economy must wear the cost of the bad debt. When the banking system was recapitalised in the early 2000s, it was the consumer who wore the pain. Deposit rates (at around 2.5%-3.5%) were held significantly lower than lending rates (6%-7%) and nominal GDP growth in the high teens was sufficient to clean up the mess for the most part. Cleaning up the banking system using the same method now would be much more problematic. GDP growth has slowed substantially, so households would be painfully aware of their financial repression.

Portfolio Implications

Structurally, there are a lot of things to like about emerging markets, of which China represents about 40% of the index. Real interest rates are positive. Economic growth in the coming decade should be much stronger. Some of the world’s most (previously) successful technology companies are also based in emerging markets. The China BATs (Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent) were seen as a credible counter to the US FAANGs.

Despite this, an inability to generate hard currency earnings has seen overall emerging markets and China underperform developed markets for the past decade. Emerging market valuations are now about as cheap relative to developed markets as they get historically. However, we think with the increased regulatory and financial market risk in China, this discount may not be sufficient.

We reduced exposure to emerging market managers in April this year, driven by concerns about China’s credit cycle and Covid response alongside some manager specific issues. We have further reduced exposure recently reflecting the concerns outlined in this update. We are now quite underweight emerging markets (of which China represents around 40% of the index) relative to our strategic asset allocation. If in response to slower growth the stimulus and credit taps are turned back on in China, we would likely tactically increase our allocation to capture the uplift. However, this would be implemented with managers who are hyper aware of the now structurally higher regulatory risk.

This newsletter has been prepared by Affinity Private Financial Services Pty Ltd (Affinity), AFSL 522707 (ABN 64 639 980 724) and is intended as general information only. In preparing this, Affinity has not taken into account any particular person’s specific circumstances, objectives, financial situation or needs. The information provided does not represent legal, tax, or personal advice and should not be relied upon as such. We recommend you obtain financial advice specific to your situation before making any financial investment or insurance decision. Where a financial product is mentioned, you should always refer to the Product Disclosure Statement and seek personal financial advice prior to making an investment decision. This newsletter contains links to third party websites over which Affinity has no control and while every care has been taken in reviewing this information, it may not remain current after the date of publication.

.