Market Update – July 2022

01/08/2022

The concept of opportunity cost might be the most important financial lesson you teach your children

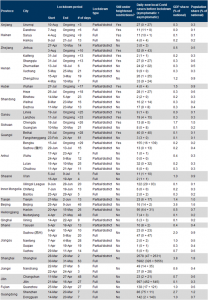

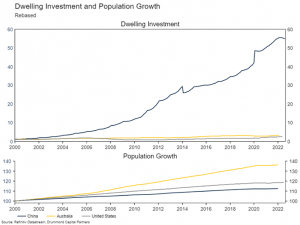

20/09/2022 Key Points: How Did We Get Here? We last wrote a China specific Market Update in July 2021, following the regulatory crackdown on Chinese technology companies and the apparent imminent bankruptcy of some large property developers. Since then, the outlook for China has worsened. In fact, so much is going wrong that this Update needs to be a little longer than normal. A key problem is an unwillingness or inability (depending on your perspective) to stimulate the economy using the tools regularly employed since the Financial Crisis. Every slowdown in growth has seen rate cuts and government infrastructure spending which, alongside a growing property bubble, have driven debt to GDP to around the same level as currently enjoyed by the USA. At nearly three times GDP, non-financial debt in China exceeds a normal level for a middle-income economy. Recognising this, periods of stimulus have often been followed by attempts to deleverage the economy. This has taken many different forms, including higher interest rates, restrictions on shadow banking (risky lending outside the banking system), state owned enterprise and local government debt reform (including allowing some defaults) and now leverage caps on property developers. However, deleveraging attempts have been stuttering at best and have often driven slowdowns in growth which necessitate more stimulus – and thus, the cycle starts again, featuring ever rising debt and capital flowing to investments with often dubious return potential. Now, yet again, growth in China is slowing sharply, but policymakers have been reticent to pull the stimulus lever in any meaningful way. This more than likely reflects an awareness of the longer-term risks from doing so. There are only so many times you can delay short term pain by embedding long term risks in an economy. Covid Policy Overhang Another key problem facing China’s economy is the continued pursuit of zero Covid. The Shanghai outbreak earlier this year was controlled through a long, strict lockdown. However, Covid cases have continued to pop up across the country, leading to heightened localised restrictions and lockdowns. As a result, citizens across the country are facing onerous testing regimes to try and prevent small outbreaks from gaining scale. For example, weekly testing is required in Shanghai and entering a public place in Beijing requires a negative PCR test within the past 72 hours. Around half of China’s 30 largest cities enforce regular or public access testing. However, this regime has not been successful at eliminating outbreaks altogether. The table below shows the lockdowns across the country since March this year. Source: Goldman Sachs Those Australian readers who lived with lockdowns and the threat of new outbreaks in 2020 and 2021 will appreciate that this situation is not conducive to a functioning economy. Consumer sentiment and spending is very weak and was not boosted as much as hoped by the end of lockdown in Shanghai. More insidiously, complete population surveillance, contact tracing and AI combine to create China’s Covid pass system, which flags and restricts the movement of users who come into contact with Covid cases. Without a green pass, it is almost impossible to operate in normal society. Simply put, there is little appetite to start a business, change jobs, buy a house, go on holiday or spend money on discretionary items when next week could hold a two-month lockdown after a handful of positive cases or when the risk of going to lunch is a personalised lockdown if someone else in the restaurant happens to test positive. Property Market Woes Housing construction in China represents a significant part of total economic activity. No one knows the exact figure, but some estimate that China’s property and related (sales, furniture purchase, finance, etc.) activity accounts for around 30% of total GDP. China also builds an astonishing amount of housing. There are around 500 million households in China and an estimated 60 to 90 million empty apartments. Some simple back of the envelope suggests at the high end around 15% of the total housing stock is empty – though it is important to note that empty dwellings are commonplace across the world. The latest Australian census estimated 1 in 10 dwellings were vacant on census night. However, for a better sense of the growth and scale in activity, refer to the figure below. Here, we show nominal dwelling investment and population growth for China, Australia and the USA rebased to the year 2000. To interpret the top panel, assume that China (the blue line) built the equivalent of one house per annum in 2000 (the rebasing). Growth in investment activity means China now builds the equivalent of 55 houses per year. In Australia, one house per year in 2000 is now three houses per year. In the US, one house per year has become 2 houses per year. Meanwhile, population growth in China (the bottom panel), has been slower than both Australia and the USA over that period. Of course, much of China’s growth in dwelling investment was necessary to accommodate a wealthier population that was moving from rural areas into the cities. The key question is whether what has been built in the past three decades is enough and what is the replacement level of investment that is necessary given China’s working age population has effectively peaked? If it is half current levels of investment, that would imply a considerable fall in overall economic activity in China given the sector’s importance. China’s property sector has been facing substantial weakness since last year when the Government enacted its ‘Three Red Lines’ policy, which essentially capped leverage amongst property developers. This policy change forced deleveraging across much of the sector, halting some projects, dramatically increasing developer funding costs, and sparking some bankruptcies. The Government has been working through troubled projects to ensure partial builds are completed so households and workers do not lose out, but it is an imperfect process. Sensing heightened risk, a number of households have gone on mortgage strike, refusing to make payments on partially completed projects they think are at risk of failure. Though this seems dramatic, so far, the absolute number has been low in a relative sense, perhaps because of the large deposits needed for a pre-sale (around 30%). A key problem is that even though the Government has eased restrictions and lowered interest rates in order to re-stimulate the sector, there appears to be little appetite from households to purchase more property. If China’s property market is a bubble, and we would argue that there is a high likelihood that is the case, it requires ongoing confidence from households that someone else will be next in line to purchase their assets at even higher valuations. This drives the inflows of capital which maintain price and activity levels. If households become worried that they will be left holding depreciating assets, the bubble could deflate, leading to a multi-year drag on economic growth and household wealth. Corporate Governance and Delisting Risks Since we wrote last year’s Insight, risks around governance in China have remained concerning. There has been some progress in terms of vocal Government support for the technology sector, but the actual regulatory overhang remains real. In July, China imposed fines on Alibaba, Tencent and a range of other firms for failing to comply with anti-monopoly rules on the disclosure of transactions. Another problem is the potential delisting of Chinese companies listed in the US due to a requirement that US regulators have complete (and retrospective) access to their audit documentation – something the Chinese Government is loath to accept. In line with the above, Chinese technology companies have continued to underperform their US counterparts since the middle of last year. The Taiwan Conundrum Last on our list is certainly the biggest risk in terms of left tail outcomes. There also does not appear to be any upside, with prospects for mainland China giving up their claim over Taiwan seemingly zero without regime change. The spectrum of potential outcomes ranges from the status quo – which probably involves some level of structural risk premium, to nuclear catastrophe, in which case portfolio positioning is irrelevant. The timing of the above is also extremely uncertain. Anything, or nothing, could happen over the next decade. A major provocation by China could be met with a variety of responses from the rest of the world, from tariffs, indirect military support or direct military support. Again, there is no way to gauge with certainty which is most likely to occur and in what order, but all are bad for emerging market expected returns should they eventuate. In line with this (amongst some other reasons outlined in the SAA Review), we removed the strategic allocation to emerging markets in this year’s strategic asset allocation review. However, we have reserved the ability to allocate tactically to emerging markets when appropriate. Cheap Valuations The other side to all of the above is that the very long period of underperformance in Chinese and emerging market equities sees those regions enjoy much better valuations than developed markets. From a price to book perspective, Chinese and emerging market equities are around as cheap as they have ever been versus developed market equities. Still, things can be cheap for a reason, and we think the reason is pretty good. There is a lot of pain to wear in China before structural imbalances are addressed and this process is still in the early stages. During its own debt deflation, Japanese equities lagged their global counterparts for many years. Portfolio Positioning We removed our residual allocation to emerging markets (an Asia fund) earlier this month. In our estimation the risk in the region still outweighs the reward, despite the improvement in valuations. The key risk to this positioning is that China’s policy makers decide the long-term risk of even greater imbalances is worth paying to re-stimulate the economy in the traditional fashion. If this scenario builds credibility, we will reassess positioning. Otherwise, the portfolios remain underweight growth assets, reflecting our expectation that major developed markets will experience a recession in the year ahead. This is prepared by Drummond Capital Partners (Drummond) ABN 15 622 660 182, AFSL 534213. It is exclusively for use for Drummond clients and should not be relied on for any other person. Any advice or information contained in this report is limited to General Advice for Wholesale clients only. The information, opinions, estimates and forecasts contained are current at the time of this document and are subject to change without prior notification. This information is not considered a recommendation to purchase, sell or hold any financial product. The information in this document does not take account of your objectives, financial situation or needs. Before acting on this information recipients should consider whether it is appropriate to their situation. We recommend obtaining personal financial, legal and taxation advice before making any financial investment decision. To the extent permitted by law, Drummond does not accept responsibility for errors or misstatement of any nature, irrespective of how these may arise, nor will it be liable for any loss or damage suffered as a result of any reliance on the information included in this document. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This report is based on information obtained from sources believed to be reliable, we do not make any representation or warranty that is accurate, complete or up to date. Any opinions contained herein are reasonably held at the time of completion and are subject to change without notice. .Failing to Kickstart an Overleveraged Economy